An analysis of dependencies to software packages in open source JavaScript projects

I recently completed my bachelor’s project and thesis. As part of the thesis work I performed an analysis on dependencies in the npm ecosystem. Since the thesis is in Swedish and therefore quite inaccessible I thought I would write up a summary in English. This post will not translate the chapter in its entirety, but rather summarize the most interesting quantitative results and some insights.

npm

I doubt anyone working on web technology has managed to stay away from the Node Package Manager (npm), a repository filled with JavaScript packages supplying a multitude of functionalities. Npm has grown at a fascinating pace and continues to do so. The rise of npm and similar repositories for other languages has resulted in new ways of building software. Developers are able to do less of reinventing the wheel and more of putting together the wheels they found through npm into really nice cars (web apps).

Having this rich set of packages available has opened up many opportunities and made it easier to create great web apps. This way of working, gluing together code written by others into a finished product, does however raise some concerns. If we are not in charge of the codebase, how can we assure quality? Especially matters of security and maintainability are of interest.

I do touch on the security concern in the thesis, but I choose to not focus on that here. Instead I recommend taking a look the work of Joseph Hejderup.

My main focus has not been to respond to these concerns directly, but rather to establish a picture of how widespread the dependency use is within JavaScript software. To see if these concerns are valid we need to further understand the typical use of dependencies to other npm packages.

Dependencies

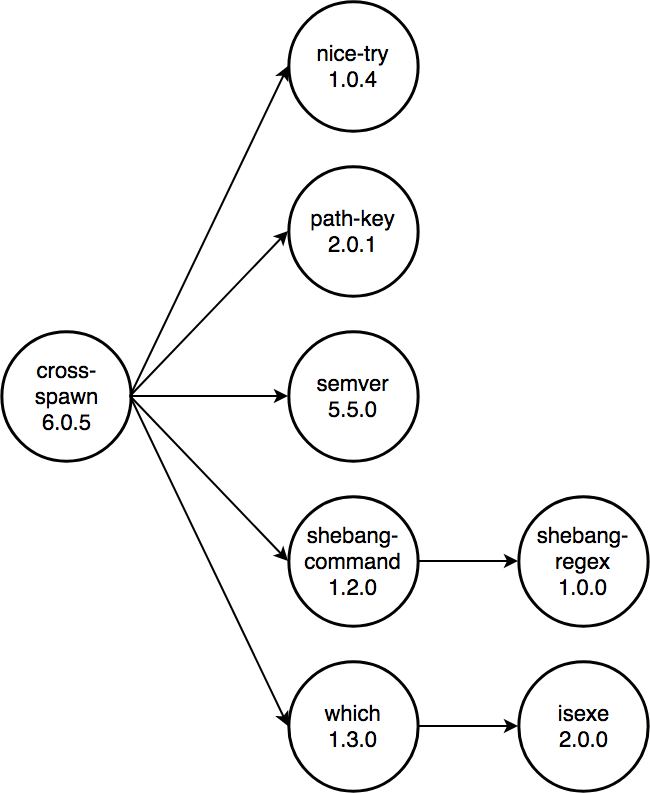

JavaScript projects using npm list their dependencies in a file called package.json. These are the direct dependencies of a project. Packages in the npm repository can also have own dependencies, subdependencies to other packages. The result of this is a directed graph structure, as can be seen below. All nodes reachable from the original project can be considered indirect dependencies.

Example of npm dependencies modeled as directed graph

Npm classifies dependencies in two different groups, dependencies and dev-dependencies. Dependencies are packaged in the final product and the code can be seen as part of the project. Dev-dependencies are packages used in the development of a project. Note for example that security concerns in dev-dependencies should generally not be considered as severe as security concerns in dependencies (although still of importance).

Method

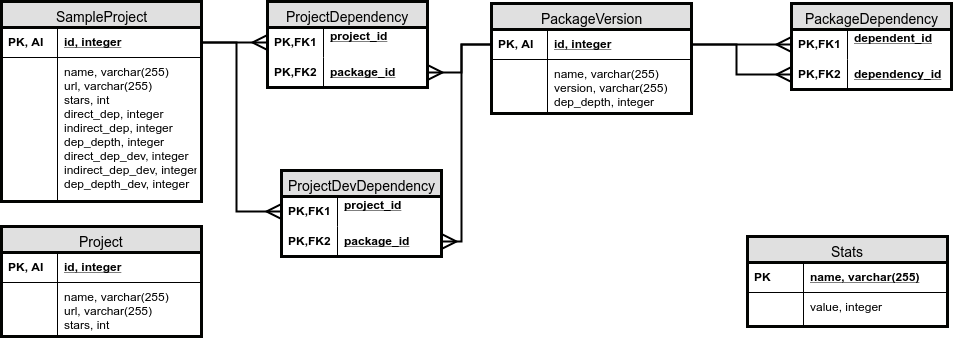

The method used was mining of software repositories. Open source projects on github were searched for package.json files containing lists of dependencies. This resulted in data on direct dependencies. For subdependencies to packages the npm command line tool was used to retrieve information. For storing all the data an SQLite database was used, as can be seen below.

This database can be seen as storing the directed graph model representing dependencies between packages. By storing package dependency data investigation of the same package multiple times could be avoided. For executing the actual analysis a Python3 script was used.

Results

The script was ran for three days, resulting in data on over 6000 projects (all JavaScript projects on github with over 500 starts rating at the time). The three statistics that were concluded from this data are direct dependencies, indirect dependencies and depth of dependency chains.

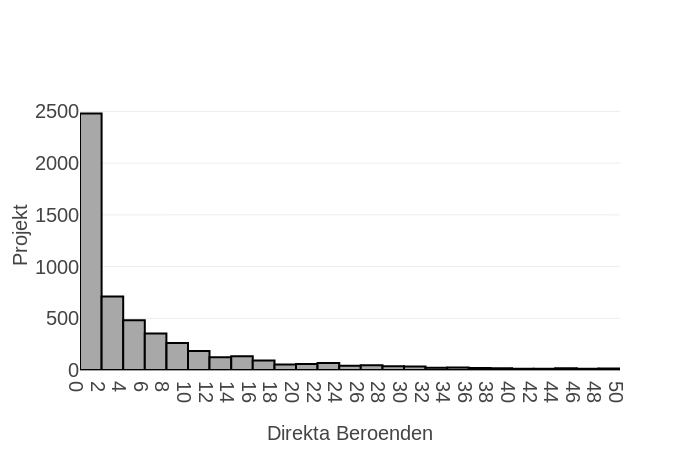

Let’s first take a look at direct dependencies. (Axis label translation: x-axis - Direct dependencies, y-axis - Projects)

It is clear that a majority of the analysed JavaScript projects have only a few dependencies. 27% had no dependencies at all. Very few have more than 20. The mean amount of direct dependencies was 6.76.

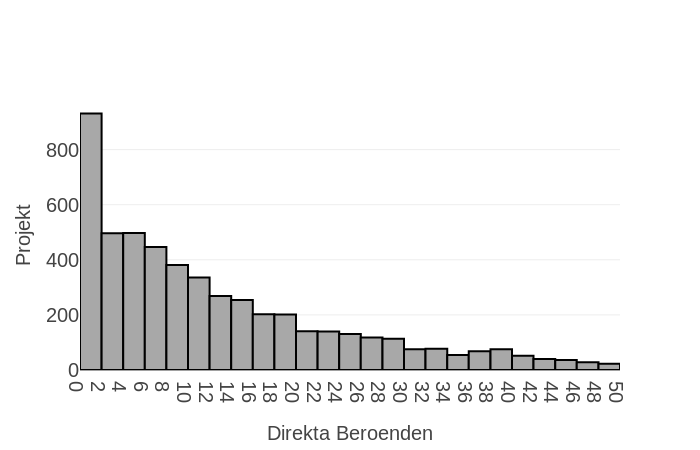

Looking at direct dev-dependencies the amounts are clearly higher. Still many projects have only a few, but the decrease in the histogram is somewhat slower. Do keep in mind different scalings of the y-axis when comparing graphs.

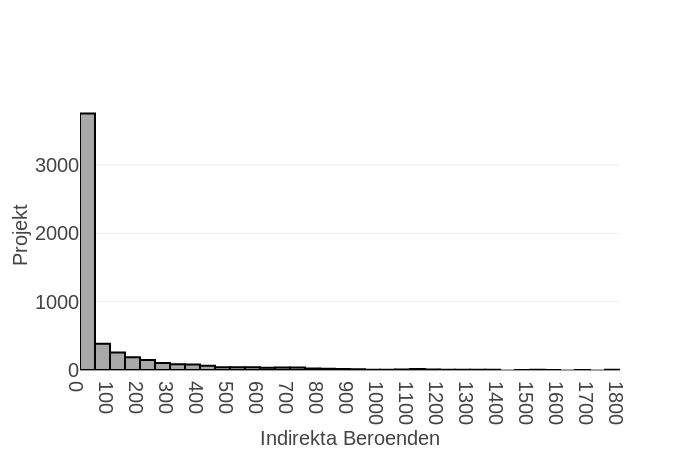

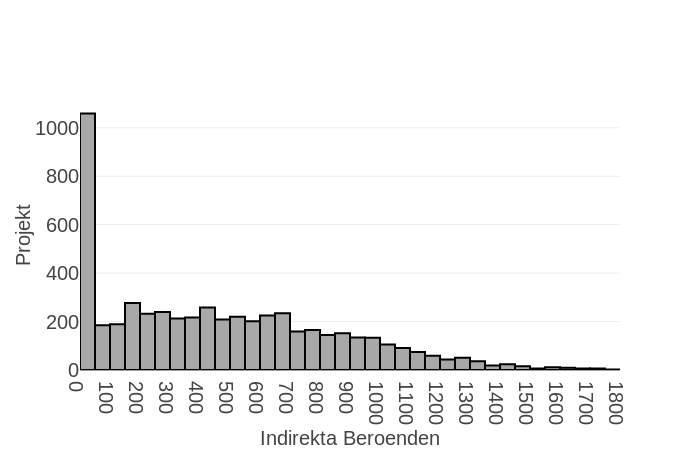

Following the dependencies of packages we get data on the amounts of indirect dependencies. (Axis label translation: x-axis - Indirect dependencies, y-axis - Projects)

For indirect dependencies we can see a similar pattern as direct with the majority of projects depending on only a few packages. Almost none seem to depend on more than 500 packages indirectly.

For dev-dependencies we see a much more flat distribution. Still many projects have very few indirect dev-dependencies. There is however hundreds of packages in the analysed set depending on more than 1000 packages indirectly.

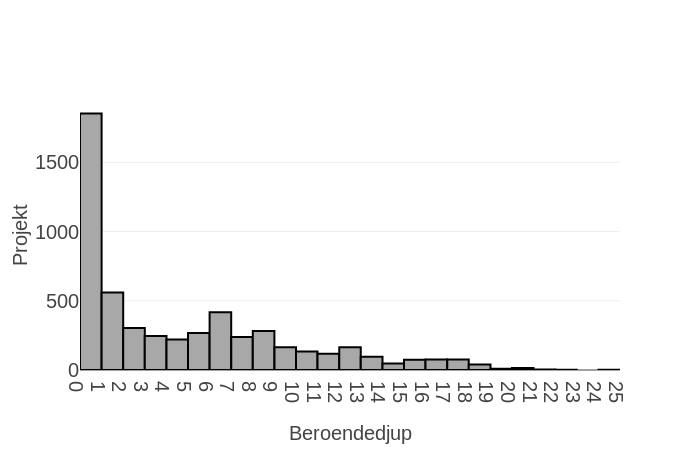

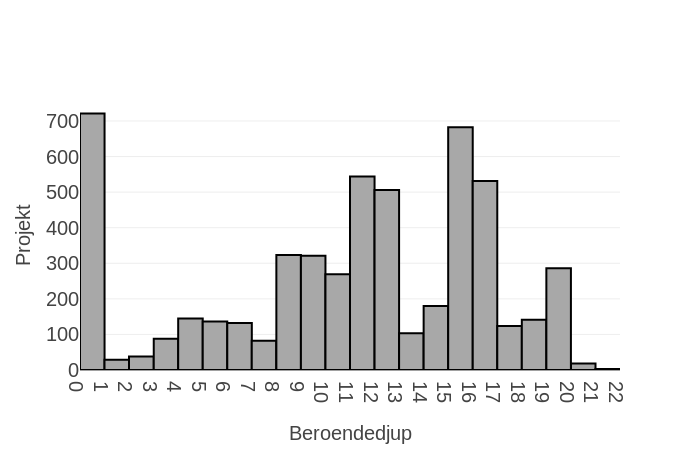

Another thing of interest is the depth of these chains of dependencies, from the project through packages to their sub-dependencies. This might give an idea of how easy it is for the developer to understand what dependencies their project actually rely on. (Axis label translation: x-axis - Dependency depth, y-axis - Projects)

Here we can see the projects missing dependencies with 0 depth. Despite quite low numbers of indirect dependencies we still see that a dependency depth of more than 10 is fairly common.

If we look at dev-dependencies it is clear that there are a some big development packages relying on many others. With almost as many packages at 16 and 17 depth as 0 it is clear that dev-dependencies can lead to massive chains of packages. Notice also how very few projects have chains of dev-dependencies only a few steps long. A vast majority of those above 0 have a length of over 7.

Some insights

There is quite some difference between the amount and complexity of dependencies and dev-dependencies in the analysed projects. It is clear that there are big frameworks often being used on the developer side, indirectly adding on a number of dev-dependencies. This might at first seem quite worrying for the quality of JavaScript projects, but it is important to consider that these dependencies have no role in the final software. One might even say that this simply indicates that JavaScript developers tend to use a lot of powerful tools (we’ll assume that is a good thing).

One of the biggest improvements (or expansions) that could be done to the analysis I think would be to categorize the examined projects. I suspect many of the projects are themselves npm packages. When considering security concerns we might mainly be interested in what would be considered end-user web applications. A problem might be that few codebases of that type are available openly for analysis. Removing all the npm packages from the data might also change the high amount of projects with few or no dependencies.

So is JavaScript software heavy and fragile from all the dependencies weighing it down and exposing new weaknesses? I would be very careful to generalise this analysis to conclusions about JavaScript software in general. What we do see in this set of projects though is quite a range of different amounts of dependencies. Still, with a direct dependency average of less than 7 any issue does not seem present here. Staying up to date with that few packages should be no issue for most developer teams. Even if we consider indirect dependencies up to 100 assuring quality even through dependencies should be possible with the right tools and processes.

For more details see the original thesis (unfortunately in Swedish). Chapter F about my analysis can be found at page 80. If you are interested in further information in English feel free to get in touch.